Will Shenton

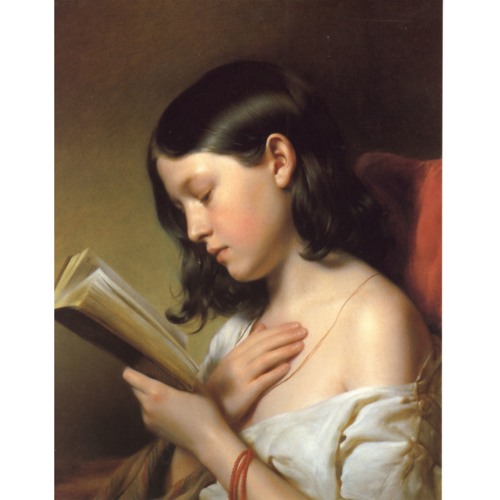

On "Cherry Mary Michigan," director Britta Lee's second music video for Slow Dakota (and, somewhat unbelievably, her second music video ever), we return to the dreamlike Midwestern landscape she explored in last year's "The Lilac Bush." Once again featuring Lee's younger siblings in costumes that place them somehow out of time, the video's impressionistic narrative serves as both a vessel for and foil to PJ Sauerteig's lyrics.

Where Lee's imagery is decidedly rural, "Cherry Mary Michigan" is a song about urban isolation. At its climax, Sauerteig laments, "Why on earth do I live in this prison / Solipsistic overstimulation / Every day, twenty-two blocks of cat-calls / Every night, twenty bills I can’t pay." We're invited to synthesize the two scenes, recognizing alienation in both the bucolic and the metropolitan. It's a conclusion we'd do well to remember: much as we may want to escape, there's no running from ourselves.